Bike on a Dyke: Further adventures of a Flaneur in the Fens

Chris Lewis-Jones

Published in/commissioned by Radical Roots literary quarterly, summer edition 2021

Radical Routes - Bitlyhttps://bit.ly › radicalroutes3

http://www.transportedart.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Radical-Roots-Issue-3-Summer.pdf

The sky. It may be something of a cliche, but it is this, more than anything else, that I notice, when I’m cycling in the Fens. Instead of shop windows, cranes and construction scaffolding, I see blue skies, grey skies and clouds. And it is the clouds that really command my attention. Towering plumes of cumulonimbus, streaks and splashes of cirrus, cotton buds of cirrocumulus…fluffy and white, menacingly dark, or shot through with shafts of sunlight, when I’m heading west, late in the afternoon, and it feels as though I’m driving through the sky.

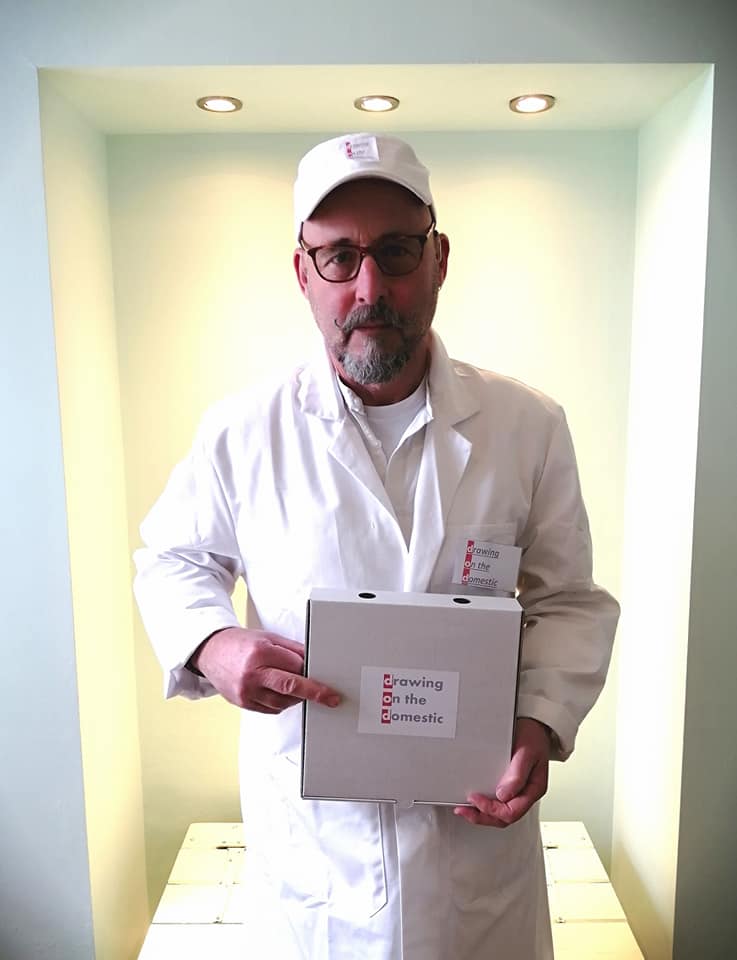

The other things I notice, as I deliver my (Drawing on the Domestic) art activity boxes to the residents of Boston and South Holland, are the accents, the relentless flatness of the landscape and, closely related to this, the extent to which I need to keep cycling in order to avoid falling over (which has taken me by surprise)!

Fenland speech seems to be so evidently shaped by the land from which it springs. The mouth opens more widely here. Perhaps it is because, unlike other places in which I’ve spent a lot of time, Sunderland, London or Nottingham for example, the air is, and has always been, fresh, a pleasure to feel in the mouth. Like the way of life, the speech here is slower. Words linger in the mouth for longer. Vowels are elongated, given more form, more notes. ‘Now’ for instance, is no longer a monosyllable. It has an emphatic beginning, a middle and an end, with a distinct ‘y’ sound appearing just over halfway through. In disyllabic words, the first syllable expands whilst the final syllable contracts, sometimes almost disappearing, especially in words ending in ‘ing’. ‘Nothing’ is almost ‘north’n’, whilst ‘finding’ is almost ‘foiyend’n’.

As I was walking along a street in Holbeach, dressed in my ‘Drawing on the Domestic’ livery, pizza delivery bag slung over my shoulder, a man called out ‘Are you a biker?’ I assumed he’d noticed me cycling around the town on my characterful little bike, or perhaps seen it folded up in the back of my car; but, just in time to answer his question, I realized he was saying ‘baker’ (not ‘biker’), with a Fenland accent! I suppose he made this not unreasonable assumption because I was dressed all in white, with a little white cap on my head. The cap could easily have been a baker’s cap, and I don’t mind being taken for a baker (I’m sufficiently post-modern to embrace these unintended ‘readings’ of my costumes)!

I relish the way that accents, like the crops in a field or the pitch of roof, change as we cross the country, especially in England’s central belt. When we are hermetically sealed in our cars we often forget this, which is why we are so easily dumbfounded on encountering unfamiliar pronunciation at the end of our journey. This seldom happens when cycling, even when we cycle quite long distances.

I find that people are far more likely to engage me in conversation when I am wearing a costume of some sort, and I always enjoy this. As I was delivering art activities to St Mary’s Church, again, in Holbeach, a man called out ‘are you goin’ fish’n’?’ What took me be surprise wasn’t so much his accent, as his assumption that my pizza delivery bag, which, to me, looks like nothing other than a pizza delivery bag, was actually an angler’s bag. I concluded from this that Deliveroo and Uber eats couriers are a less common site here than anglers. This may not be a profound observation, but signifiers of difference are always interesting, to a flaneur anyway!

Towards the end of the Drawing on the Domestic Project, I cycled from my hotel in Boston to the Pilgrim Fathers’ memorial, 3 miles or so down the Haven. Here another man (interestingly, no woman, as yet, has called out to me to justify my attire!) shouted out ‘You have a good day there fella!’ He had a big smile on his face and continued to glance back in my direction, calling out encouraging remarks as he strode along the Dyke. He didn’t know what I was doing but recognized in it something that he felt to be, in some way, positive, and worthy of support. Given that I had toothache at the time and felt in need of support, undeserved though it was, it was much appreciated!

The influence of lowland Scotts in the area around Corby in Northamptonshire is clearly discernible. The influence of Jamaican English on contemporary London English is similarly apparent. However, the influence of Slavic pronunciation on Fenland speech remains to be seen. It must already be happening in the playgrounds of Spalding, Boston and elsewhere, but I’ve yet to hear it. Whatever its effect, it will, surely, enhance the richness of the local English, and inform the narratives through which we come to understand who we are, where we are, and where we are from.

In my hometown, cycling anywhere north of the Trent entails a mixture of up-hill exertion and downhill exhilaration. There is no uphill or downhill in the Fens, so, although I don’t miss the exertion of struggling uphill, I do miss the exhilaration of whizzing down. It may appear counterintuitive, but cycling in these flat lands feels more like hard work than cycling in undulating Nottingham. Here, if you stop peddling, you stop moving. I can’t help but see this as metaphor, illustrating the extent to which the landscape itself (like cycling) requires constant effort. In order for the land to remain terra firma, a huge amount of effort has to be put into the pumping and diverting of water from what would otherwise be the North Sea. This effort is evidenced by the abundance of dykes, sluices, locks and drains that are the defining characteristics of this man-made region. As Greg Russell sings on Danny Pedler’s Water Makers this Land (on Field and Dyke, an album inspired by the tales of South Holland folk):

‘water made this land somehow; water makes the land still now’.

The struggle to maintain the land is intensified by rising sea levels, a consequence of climate change. The situation can only worsen, so the struggle will continue, until the North Sea wins.

Having been raised in the shadow of A E Houseman’s ‘blue remembered hills’ (Malvern, Clee and the Cotswold) and having lived most of my adult life within striking distance of the Peak District, I was initially skeptical about the attractions of the Fens, equating flatness with dullness. At least it’s near the sea, I mused. However, I was frequently disappointed by the apparent absence of anything resembling the coast, or even hinting at its proximity. Getting to the coast between King’s Lynn and Skegness is problematic. There are no resorts, other than Skeggy, and there are no coast roads. If you can be bothered to navigate your way through the C class roads and tracks that eventually end at the Wash, you’re still likely to be a mile or two away from the wet stuff, twinkling mockingly in the distance, across acres of pink mud. Sometimes I have glimpsed what appear to be estuarine lakes, or tidal inlets, glinting invitingly in the distance. However, having raced hopefully towards them, these have turned out to be lakes not of water, but of vast sheets of cloche plastic!

Notwithstanding the above observations, I have come to appreciate the drama of these flatlands and have grown genuinely fond the area. When you do make it beyond the C class roads, to those endless acres of pink mud, surrounded by the resident avian choir: crying, laughing, screaming and keening…it is indeed a wonderful experience…a wonderful place in which to relish solitude.

As I cycle past enormous fields, beneath enormous skies (with an enormous courier bag, precariously perched on the panier of my diminutive bike) I find myself ruminating on the liminality of it all…the Fens, the coast, the accent, the economy…especially in the face of climate emergency and a global pandemic. Economic precarity had already penetrated deep into these isolated communities, so the effect of Covid and its accompanying lockdowns has impacted hugely on their way of life. A life lived, increasingly, on the edge: physically, socially and economically.

Since the demise of the port of Boston, which was connected (via the Hanseatic League) to a string of ports along the Baltic, North Sea and Atlantic coasts, the area to the east of the A1 and the south of the Humber, not being on the way to anywhere else, has felt somewhat out on a limb. According to the state, Lincolnshire is now part of the East Midlands. Traditionally, the area known as the midlands wasn’t just centrally located, it was land-locked; by definition, it had no coast. I’m inclined to agree with locals, from both Boston and South Holland, who have told me that they reject the idea that the area in which they live, or anywhere else with a coastline, could be considered to be part of the midlands. So, where does that leave the Lincolnshire Fens? The ‘local’ tv news is broadcast from Hull, Nottingham or Norwich…hardly local! Is the area part of the East Midlands, greater Yorkshire, or greater East Anglia? I feel it occupies a liminal space, not only between the land and the sea, but between the greater north and the greater south. It is neither one nor the other, but, depending on your terms of reference, could be either.

It used to be joined to the continent by Doggerland. Mesolithic families walked over Doggerland, from the Fens to Europe, as far as the Pyrenees and back. We know this because of the artefacts they brought back with them. As the oceans rose, the area was, once again, submerged, and Britain became, for the first time, separate from the continent of Europe. To many in this part of the world, that was, and is once more, a good thing. As the oceans receded, patches of rich loamy land began to emerge and were settled. Neolithic potters, iron age shepherds, Celts and Romans, Saxons and Danes…attracted to the fertile land with access to the sea, left their place names and their routes for us to inherit and to enjoy. Saxon outlaws sought sanctuary in the Fens’ reeded islands from genocidal Norman overlords. As relative peace returned, merchants from the Hanseatic ports, across the North Sea and the Baltic, began to arrive, first as traders, then as settlers. Dutch migrants brought their engineering skills and their gable-ends. As more of the land was drained, immigrants from elsewhere in England and, more recently, from Eastern Europe, came to work it.

Cycling past teams of workers, probably Eastern European, laboring like ants in the vast fields, I am overtaken by other Eastern European workers, driving lorries back to continental Europe, with containers packed with produce processed in local factories by other Eastern European workers. If I pop into a corner shop, it is highly likely to be run by (and not just for) Poles, Russians, Latvians or Ukrainians, perhaps Kurds, Cantonese or Punjabis. I appreciate this cross-continental web of commerce and culture as I pass kitsch cafes selling instant coffee in plastic cups, artfully arranged KitKats in decorative baskets and cellophane-wrapped rubber sandwiches…with union flags fluttering from the plywood windmills and portals of tanks (yes, tanks) that decorate their forecourts. I pass clusters of bungalows with chocolate-brown bricks and white plastic windows, in villages that are a thousand years old or more, with only churches and street patterns to remind us of their ancient heritage. Villages in which the villagers have forgotten how to sing or dance the songs and dances of their ancestors. I feel the poignancy of the liminality of it all: the land, the sea, the land again…the Celts, Romans, English, Danes, Normans, Poles, Russians, Bulgarians, Kurds…

With its universities, societies and centres of culture and governance, the city tends to think it has all the answers, but here, in the windswept Fens of eastern England, the mutability of the landscape and the cultures that shape and are shaped by it, remind us that life itself is lived in a state of Flux. The past is a fiction, the future a dream. Nothing is fixed. Not the coastline, not the accent, not the land, not the economy, not the climate. Change is inevitable, flux is positive. Without flux, there would be no diversity, no late-night takeaways, no progress, and, more to the point, no Fens.